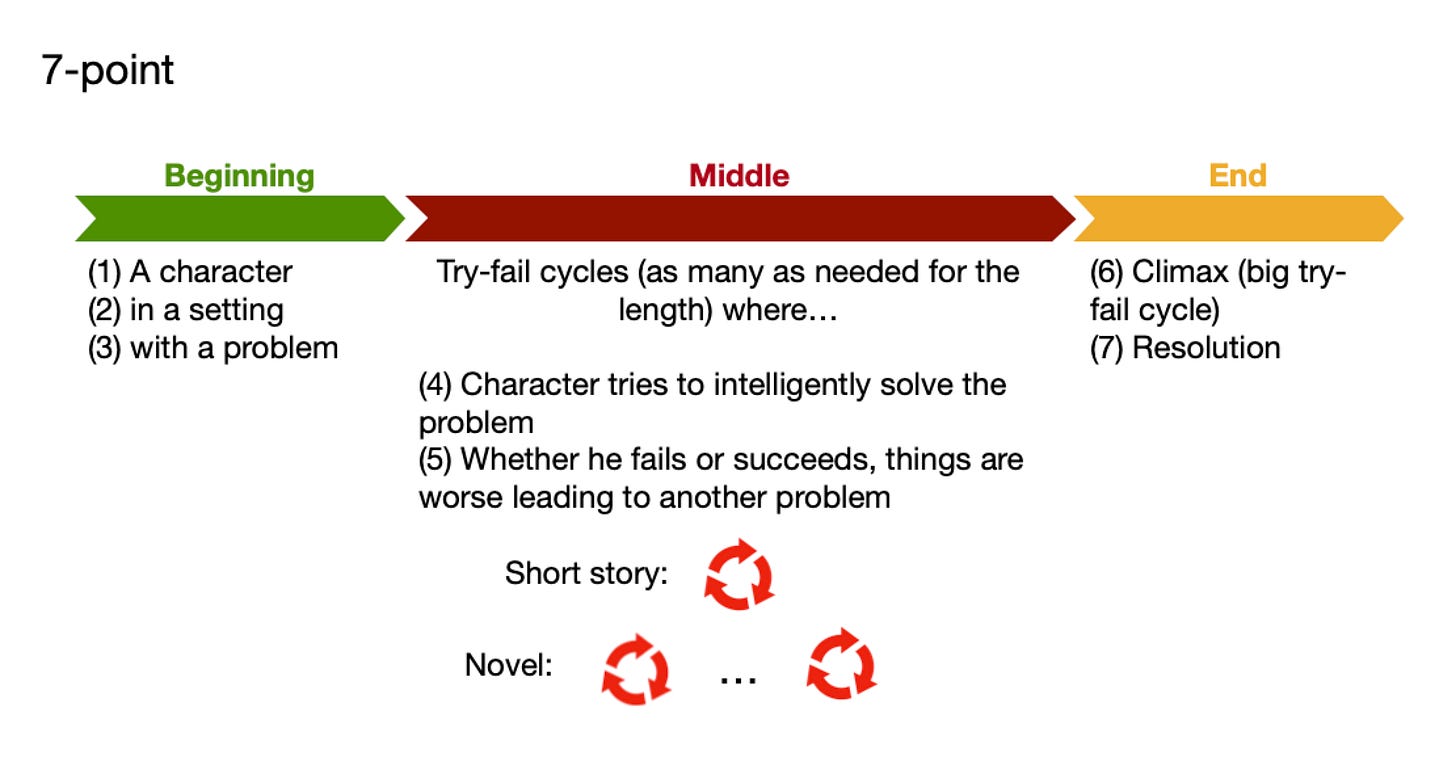

Previous post: The 7-point plot method (part 2)

The last quarter of a story, the ending, is made up of the climax (a big try-fail cycle) and the resolution.

As I pointed out before, the vagueness of this 7-point method does not tell us much about what goes into making a climax or a resolution.

In the simplest of terms, the climax is just another try-fail cycle that happens to be the very last one.

Let’s revisit, Billy, our young hero:

Billy is a sweet little boy who lives in Suburbia and he desperately wants a bicycle because if he doesn’t get one he has no way to visit his sick friend and the overzealous Karen running the Suburbia HOA calls CPS on his parents whenever he is out by himself.

The climax, hopefully consists of Billy succeeding either at getting a bicycle or at finding a way to visit his friend despite Karen.

Based on “no matter what, things get worse” you’ve got your try-fail cycles set up in a way where things got progressively harder for Billy.

Sitting here thinking about it, it’s easy to imagine the obvious route. Billy mows some lawns. Billy gets paid. Billy gets a bike. Billy rides over to his friend’s house. Now, if you’re too wrapped up in “Why doesn’t he just call/text/video his friend?” then you’re missing the point of this exercise. Obviously he can’t just call/text/video his friend because of the milieu or story circumstances. Obviously the world-building aspect of this limits his options in some way, i.e. this story takes place in the 1980s or something. Maybe his friend is Amish and they don’t have a phone. The try-fails still need to do what they need to do in concert with the milieu/circumstances, i.e. fiction has to make sense.

But the sequence of gets paid, gets a bike, rides over, did not meet the criteria of “no matter what, things get worse.” If that’s all it takes, then Billy is our very own suburban Gary-Stu even if he works for the bike (i.e. it’s not just given to him) because he succeeds easily. This tendency to succeed (rather than fail or to make things worse even if things go his way) is what ruins the ending, no matter how clever or unique.

Here, as we segue into the climax, we should be chomping at the bit to see if he can win. Ideally you want us going into the climax rooting for Billy, hating Karen even more than we already did, and having set things up in a way that we believe he could fail. Making readers believer that he could fail comes from the middle try-fail cycles where “no matter what, things get worse.” Which means that you as the writer have to be willing to use Billy as a piñata. By this point Billy should be hating your guts (if he was real and knew of you).

So one problem with endings is that we don’t go into them believing he could fail. After all, we’ve seen him win and win and win again. We’ve seen Gary-Stu and Mary-Sue solve problems easily and predictably. If we’re still reading at all, it’s for some other reason, not because we are dying to find out how he solves the problem.

The other problem with endings are the surprise endings. An ending should be a “surprise” in the sense that it’s plausible but not obvious. In retrospect (i.e. after you read the ending), you should be able to go “aha, that makes sense, why didn’t I see it?” not “Huh? Wut? Whoa, what did I miss?” If you go back and re-read to see what you missed and what you missed is there, then it’s on you. If it turns out you missed nothing, then it’s on the writer.

This is where some writers will pull vampires (or some equivalent) out of their … hmmm… air (yeah, that’s it, air) and go “Surprise!”

Please don’t do that. This is the dreaded deus ex machina ending.

As a pantser I rarely set out knowing how the story will end. I have an idea of what I want out of it. Usually. In this case, I want Billy to win and Karen to get her comeuppance. The problem is that Karen getting her comeuppance and Billy winning can take several forms and they are not all valid choices.

For example, Karen getting killed by vampires as a deus ex machina ending is less than satisfying. Unless…

Unless Billy’s try-fail cycles consist not of mowing lawns and trying to earn money for a bicycle, but of sneaking out at night to find said vampires and convince them to eat Karen. If my try-fail cycles consisted of this, it’s not a deus ex machina ending at all. It also may not make Billy a hero (the person that facilitated the solution to the story problem). Depending on genre, Billy doing the deed himself may matter.1

Also, something bad can’t just happen to Karen. Something bad has to happen to Karen because of Billy’s choices or actions. Given the age disparity, this can be hard to set up. Billy speaking truth to power may be a popular choice in YA but does it make sense in your story?

Maybe the climax is just him showing up at the HOA meeting and giving a speech about it and now the deputy who has been taking the calls and chasing Billy down comes over on Billy’s side. Or the other residents do. If that’s your ending, the middle should at least hint at all of this. If the middle part was all about him mowing lawns, speechmaking will fall flat. He can’t just show up at the HOA, covered in lawn clippings and go into YA/NA-protagonist mode.

We should get an idea that the other residents are on his side or that the deputy is. Or that he’s been working on his speech as he mows and this is a world where all you need to do to change things is make speeches2, in which case we’ll all be wondering why no one has and Billy is having the problem in the first place. A speech is an easy try-fail cycle that should have been the go-to at the start and hence, there is no story. Now do you see the problem with this method?

Maybe the climax is that the deputy decides to give Billy a ride over to his friend’s house, whenever he wants. But then it’s not Billy solving the problem is it, any more than having vampires swoop in is. Then the story is about the deputy and his struggle to break the rules by doing this. Billy is a side character, not your protagonist.

My point here is that no matter what the climax is, no matter if it’s something you know ahead of time or not, it has to flow out of the middle, and out of the milieu you built. It has to make sense. If it doesn’t, you need to cycle back and fix the middle or you have to fix the ending. And you may end up going back and forth several times in order to make these two pieces click together in a way that works. This is why even when we talked about the Big, Swampy Middle we had to keep the end in mind and now that we’re talking about the ending we have to talk about the middle. They are inseparable.

Also, don’t forget: It is a fact that while reality doesn’t have to make sense, fiction does. YA/NA, and your “Strong Female Characters” notwithstanding.

One of the more common problems I see is that the writer has a really cool idea for the climax, but rather than building up to it, they play “hide the weasel.” They have a bunch of middle-part try-fail cycles, few or none of which have much or anything to do with the story solution (the climax) and then the climax consists of Billy revealing that he had an ace up his sleeve all along, an ace he never once thought of or hinted at or developed. This is your YA character who’s been clumsy and uncoordinated all along suddenly having killer jiu-jitsu skills for the ending. This is your Gary-Stu jumping out of the pit of despair after spending the whole story not telling us about his amazing jumping superpower. I see a lot of this in “the pulps” where the protagonist knew something all along but never thought of it until the end or the omniscient narrator never mentions it until the end because that’s the only way to pull it off and it feels like a cheat because it is.

Or it turns out that Karen was his mother! This is not a getting stuck problem. This is a bad storytelling problem.

Psst: This is why an idea is not a story.

One of the reasons I abandoned the 7-point plot method—yes, even for shorts—was specifically because it didn’t help me with setting up the ending in a satisfying manner. For when I am well and truly stuck, it often fails.

For when I already have some idea of the short-story ending, it’s still useful. I just check myself mostly with word-count compliance and whether or not the try-fail cycles make sense and lead to the ending I have in mind. I don’t find it particularly useful for any long-form anymore. Like a dull knife, I’ll stick it in the junk drawer and use the better, sharper one instead.

But one of the reasons I wanted to start with the 7-point method is that it can be useful, even when pantsing, not just for story-level pacing but for a basic method that will then allow you to segue to more sophisticated methods. Or maybe get your subconscious (your pantsing brain) thinking in terms of building up to the climax so that next time it’s a little easier and you have less rewriting or cycling to do.

The way things work (or should work) is that as you acquire skills and internalize process, it gets easier. If it doesn’t, then there’s another problem in play, one beyond the scope of this series.

As far as the resolution goes, it’s mostly about tying up or acknowledging loose ends. Often the tying up/off is in summary form rather than dramatization, and its goal is to give the reader a sense of closure. This is the part where Chewbacca and Lando tell Princess Leia that they are going after Han (the loose end being tied up/off in ESB). Despite being dramatized rather than told in summary it is short and just one of the threads that was tied up after the climax (where Luke lost his hand).

Next, we’ll tackle the 3-act method which is more involved. One of the reasons I like it so much better than the 7-point plot method is because it actually defines what a climax and resolution are and how everything preceding them should tie into them not just overall, but at specific points in the story.

Thank you paid subscribers. To access articles more than four weeks old, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

There is another nuance here that is not addressed by the 7-point plot but that I won’t really go into right now. It has to do with how much help did Luke Skywalker really have? He didn’t kill the emperor did he? So does that mean that Darth Vader is really the hero?

Likewise one of the many complaints I see in the Anita Blake fan groups is the number of times that Anita doesn’t participate in the solution because she passes out. Even when it makes sense for her to pass out and for others to actually carry out the solution, fans complain. They feel cheated. Something to keep in mind.

Say it with me: I am not Ayn Rand. I am not Ayn Rand. I am not Ayn Rand.

Thank you for the time and effort you put into clarifying the different outlining methods, Ms. Monalisa. The way you lay this out has finally, finally enabled me to grasp what others have tried to explain before. It may be repetition that leads to breakthroughs, but the way you break things down flows so much better, IMHO.