Previous post: The 3-act plot method (part 1)

If you’ve not read the previous posts, I highly encourage you to do so, or the rest of this might not make sense.

One of the reasons that the Big Swampy Middle is called that, is because it is big, comprising half the story/word-count and its swampiness comes from the fact that it must bridge the beginning and the ending in such a way that it gives the reader a sense of satisfaction. That sense of satisfaction can be complex and individual, but it’s not as mysterious or taste-based as some would argue.

As with Act 1 (The Beginning), Act 2 (the Big, Swampy Middle) is made up of certain elements. In the middle-school understanding via the 7-point plot, it was made up of an indeterminate amount of try-fail cycles with the cryptic requirement that “no matter what, things get worse” but with no details or specifics in regard to anything but events, i.e. no character development concerns, etc.

The 3-act method remedies that vagueness with the following (again, from Katie Weiland’s excellent books on structure):

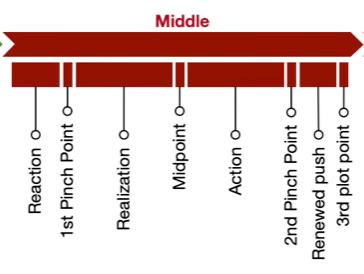

Act 2 The Middle

Reaction (25-32%)

1st Pinch Point (33%)

Realization (34-49%)

Midpoint (50%)

Action (51-65%)

2nd Pinch Point (66%)

Renewed push (67-74%)

Third plot point (75%)

For the details, I again refer you to her books and workbooks as well as the articles on her website.

So now our middle is no longer just about try-fail cycles, but about try-fail cycles that also have be paired with reaction, realization, action, and renewed push. This takes advantage of the scene-sequel process where “scene” refers to action as in something happens, and “sequel”1 refers to the aftermath or reaction/response to that action (which may be an event, rather than “action” as in Hulk!Smash!).

We ended Act 1 with a turning point that changes everything for the character and begin Act 2 with their reaction to it.

Then the first pinch point is an incident that tests the protagonist, i.e. it’s a try-fail cycle or part of one. The character attempts to intelligently solve the problem and whether or not he succeeds, it makes things worse.

Then he realizes things have gotten worse and reacts or responds to it.

It is followed by the midpoint, which is a turning point, just like the end of Act 1, where something causes change in the character. That midpoint is also a try-fail cycle, or part of it. But specific things have to happen in order for it to be a proper midpoint.

And after the try-fail cycle that is also the midpoint, there’s a reaction to it (one called ‘Action’ ; you’ll see why below).

The next try-fail sequence (notice I didn’t use the word “cycle”) is known as the second pinch point.

Then the reaction/action that comes due to it is the ‘Renewed push’ which leads to the third plot point, a major turning point.

The main takeaway from this method is that pinch points are minor turning points while plot points are major ones.

There is also a built-in “rule” about using the pinch points to foreshadow or signal the final act solution and having it be about the main plot, not a subplot. And by specifying that after each plot point and pinch point, there is a requirement for “reacting” or “responding” to it, it forces the story into a mold where the protagonist (and thus the reader) gets a chance to catch his breath so they’re not rushing from event to event (try-fail cycle to try-fail cycle) and exhausting the reader.

The Big, Swampy Middle looks a lot less swampy this way, doesn’t it? As before, I am not telling you that the midpoint needs to be a short scene squeezed in between two longer scenes, the Realization and Action. What I am telling you is that it should be as close to the 50% mark as possible and be preceded by the Realization and followed by the Action. And that it may take several scenes to realize the “Realization” and that the Midpoint may be part of a longer scene that is also part of the “Realization” and/or the “Action.”

Act 2 The Middle might be understood in this manner:

Reaction (25-32%) is the reaction to the big chance that Act 1 ended with; opportunity to develop character

1st Pinch Point (33% aka 3/8th mark) ← a try-fail where things get worse; signals solution

Realization (34-49%)← reaction to the 1st pinch point; opportunity to develop character

Midpoint (50%) (aka Second plot point aka as the 4/8th or 1/2 mark) where another big change occurs and has specific consequences

Action (51-65%) in regards to the midpoint, i.e. a type of reaction; opportunity to develop character

2nd Pinch Point (66% aka 5/8th mark)←another try-fail where things get worse; signals solution

Renewed push (67-74%)← reaction to the 2nd pinch point; opportunity to develop character

Third plot point (75% aka 6/8th mark) where another big change occurs that segues into Act 3

There may be other smaller try-fail cycles mixed in, so don’t interpret this as only needing two try-fail cycles (at the 33% and 66% points). Those points are called out only because they must do specific things, i.e. signal/foreshadow the third act solution.

As an exercise for those who are playing along, I challenge you to look at your story’s middle with an eye toward whether or not your try-fail cycles at the 33% or 66% mark signal/foreshadow the third act solution. Also look at whether or not your First plot point (at the end of Act 1; the 1/4th mark) and your Second (Midpoint; the 1/2 mark), and your Third plot point(the 3/4 mark) meet the criterion of “Big Change.”

If you have a shorter short-story this may be too specific, but if you have a longer one or a novellete or novella, I think this can be useful, especially in regards to the turning points. Why? Because the First plot point (end of Act 1 at 1/4), the Second (Midpoint at 1/2), and the Third plot point (at 3/4), have to do with changes that drive your character to the ending and give him an opportunity to fail and thus to grow. Failure is key. Failure is required.

So let’s take a look at Star Wars via Weiland’s Story Structure Database:

At the end of Act 1 in Star Wars, Luke fails to save his aunt and uncle, an event that drives him to go rescue the princess and become a Jedi (not defeat the Empire, not destroy the Death Star, i.e. we don’t yet have the big story problem). At this point his reasons are selfish. Relatable, but selfish.

Now look at the First Pinch Point:

First Pinch Point: After hiring passage out of the Mos Eisley spaceport aboard Han Solo’s Millennium Falcon, Luke and Obi-Wan are chased off-planet, under fire, by Imperial Star Destroyers.

The true pinch comes in the subsequent scene when Grand Moff Tarkin and Darth Vader use the Death Star to blow up Alderaan while forcing Leia to watch. It’s a skillful demonstration of their true power and a foreshadowing of the climactic conflict.

But note how the plot’s turning point—Luke’s escape from Mos Eisley and the beginning of his journey to Alderaan—is also nicely “pinched,” thanks to the antagonistic presence of the pursuing Star Destroyers. — Story Structure Database

Do you see the planting/foreshadowing of the Third Act Solution? It’s not just a “pinch” point because the Falcon is being chased. Several scenes make up the Pinch Point, including one where … Tarkin blows something up, i.e. just like in the Third Act Solution. The involvement of the Death Star foreshadows its own demise. And you guys thought this was just a fun popcorn movie without any literary plot devices.

Now look at the Second Plot Point aka Midpoint:

Midpoint: After emerging from lightspeed at the coordinates where Alderaan should have been, Luke and Co. encounter the Death Star for the first time. The Falcon is pulled in by a tractor beam, and they barely escape by hiding in Han’s smuggling compartments. Afterward, Luke discovers Leia is a prisoner aboard the Death Star. He and Han shift out of reaction and into action by deciding to go rescue her.—ibid

The Midpoint is all about shifting out of reaction-mode into action-mode. Not action as in lightsabers and Hulk!Smash! but as in who is calling the shots. Up until now it definitely wasn’t Luke, was it? Ben, yes. Han Solo, yes. All the people chasing them call the shots at one time or another. But never Luke. What happens in the prison ward?

Luke may not be calling the shots (yet!) or for long, but he is at least doing “Action” rather than “Reaction.” A better term might be “Reactive” for the first half of the story, and “Proactive” for the second half, which is something we’ll tackle in detail in the 4-act method which is much better suited for this type of storytelling.

As for the second pinch point:

Second Pinch Point: After the rescue goes sadly awry, Luke, Leia, Han, and Chewie are forced to hide in a trash compactor. This proves to be a dangerous mistake, when a dianoga sewer slug tries to eat Luke and the Imperials then turn on the compactor in attempt to crush them. They barely escape, thanks to Artoo’s intervention.—ibid

One can argue that this foreshadows the third act solution as well. They have to—gasp!—shut something down. Just like in the third act. Was it deliberate/conscious on Lucas’s part? I have no clue. Maybe someone can speak to that. But it is there even if the consumer is not conscious of it. Instead his subconscious is, i.e. that Story hardwiring that’s running in the background.

Reverse engineering note:

The nice thing about cycling (whether you’re pantsing or plotsing or outlining) is that once you get to that third act solution in your Story you can cycle back and make sure that your pinch-points foreshadow the solution. Yes, yes, you must rewrite. And if you planted it without even realizing so much the better. I do this sometimes because I subconsciously know what the ending will be as I’m pantsing. But when I don’t subconsciously know it, then I cycle back and make it forward- and backward-compatible. I rewrite. I fix. I make it better and I make it work, sometimes ruthlessly cutting or rewriting thousands of words because word-count (BICHOKing) is not what makes a story work.

The Star Wars Second Pinch Point also touches on the “in the belly of the beast” or “the cave” aspect of storytelling technique, thereby meeting multiple requirements of Archetype and Trope (something for the 4-act method).

If you’re having trouble seeing these things, I understand. It’s hard to shut off the consumer aspect of Story and really look at the underlying guts of it, the sausage-making as it were. But if you’re going to be in the business of making the sausage, that is your entry fee.

As for the Third Plot Point (at 3/4, the end of the Big, Swampy middle), it’s another big change, one with an additional refinement: The low point. This is the “dark moment of the soul” from which the hero must rise and not just another try-fail that happens to be the penultimate one.

So now that we have a little more refinement for the Big, Swampy Middle, we are ready to tackle the refinement of Act 3, and that’s where we’ll pick up next time. After that, we’ll get into the 4-act method which adds even more refinement, particularly to the elements that make up the beginning.

Thank you paid subscribers. Your valuable support is always appreciated.

The “scene-sequel” method is its own thing and has nothing to do with sequels to stories or with scenes in stories. It only ties into the traditional understanding of a scene as a unit of prose or a sub-unit of a screenplay in that both the “scene” from the scene-sequel pair and the “sequel” could be scenes. I know it’s confusing. It’s not my fault. Blame English. Blame the writing world which loves to use the same words in many different ways, a la ‘beats’. We can’t get enough of those either. Physical beats, dialogue beats, story beats. Same with plot points. They mean different things in different methods. It’s enough to set your hair on fire. Disclaimer: please don’t actually set your hair on fire.

“Pinch Points are minor, and Plot Points are major turning points.” For some reason that wasn’t clear to me after reading her workbooks, books, and websites. 🤦♂️ Ms. Weiland’s descriptions should have started with this statement. I was too focused on making the antagonist or the antagonist’s effect appear at the Pinch Point instead of seeing that the antagonist was always there in some form throughout the story. Thank you for clarifying this, Ms. Monalisa. 🙇♂️ Also, thank you for posting these supplemental details for your lesson at P-Con. This method works especially well for me. The repetition/resonance from that day forward has been more helpful than the string of writing advice books I’ve muddled through on my own over the past two years.

Good advice, as usual. Now the hard part is figuring out how I can implement it.